Transcript

Anne Holsinger 0:01

Hello and welcome to Discussions with DPIC. I’m Anne Holsinger, Managing Director of the Death Penalty Information Center. Our guest today is Elisabeth Semel, Clinical Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley. She joined the Berkeley Law Faculty in 2001 as the first director of the school’s death penalty clinic, and remains co-director, Professor Semel and her students have represented individuals facing the death penalty and filed amicus briefs in death penalty cases before the US Supreme Court, including cases related to racial discrimination in jury selection. Thank you for joining us, Professor Semel.

Elisabeth Semel 0:36

Thank you so much for inviting me.

Anne Holsinger 0:38

Could you start by describing your work at the clinic and what makes it unique?

Elisabeth Semel 0:42

I don’t know that I would describe us as unique but certainly, capital punishment clinics in law schools are unusual. There are only a handful of us across the country and there are several things about the death penalty clinic at Berkeley Law that probably are unique. First of all, our students are enrolled for entire year. All of them, for the last number of years, have been in their last year, their third year of law school. We represent clients at all stages of the capital proceedings. Some of our clients are pretrial. Some of our clients, although less often, we take cases on what are called direct appeal, the appellate process, many most of our clients are in post conviction proceedings. Another unusual feature of the death penalty clinic here is that although we are located in California, the majority of our clients are in the south and we have represented clients in a number of southern states such as Alabama, Georgia, Texas, Virginia, and Louisiana. The focus of the clinic’s work in direct representation, since it launched, has been to provide legal representation in those states with the most limited resources that are active death penalty states, by which I mean states that are actively carrying out executions. In the last five or so years, we have returned some of our attention to the state of California, because of some very important opportunities to make systemic change, systematic and structural change in the way that race discrimination has been such a- such an important and destructive influence in not just the capital punishment system, but the legal, criminal legal system as a whole.

Anne Holsinger 2:32

As we’re releasing this podcast on April 30, that marks 38 years since the US Supreme Court announced a new test in Batson V. Kentucky, as a way for criminal defendants to challenge the exclusion of potential jurors because of their race. I know this is an area of the law that you’ve followed closely. How do you assess the impact of this case?

Elisabeth Semel 2:53

I would answer your question by grading Batson versus Kentucky with an F, also with the word failure. It certainly has failed to achieve its promise. Its promise was to eliminate race discrimination in the exercise of peremptory challenges and we can talk about what that means, but it has failed the defendants who have been tried since Batson. And by that I mean, particularly defendants of color, and it has failed prospective jurors, that is citizens of this country, especially Black citizens, in their right to serve as jurors in criminal and civil cases.

Anne Holsinger 3:32

Could you explain a little bit about what peremptory strikes are for our listeners?

Elisabeth Semel 3:35

Certainly. So in a trial, whether a civil trial or a criminal trial, cri- if you think of a criminal trial as something that can result in the loss of liberty or life, or money. The attorneys in the trial have two kinds of challenges, two ways of requesting that a prospective juror be excused. The first is what’s known as a challenge for cause and that requires the lawyer to show some reason why the particular juror cannot be fair in the case – has a bias. A simple example would be a juror who is related to the judge in the case cannot be fair because of that relationship. Peremptory challenges allow the lawyers to remove – we use the word challenge or strike – a number of jurors without any reason, for no reason at all. In the case of cause challenges, lawyers have an unlimited number of opportunities to raise and have a judge rule on a cause challenge. In peremptory challenges, every state is different, but the easiest way to understand it is that each state typically has a statute or rule that gives each side a set number of peremptory challenges. So in California, for example, the defense and the prosecution have 10 each peremptory challenges in a felony trial and 20 in a capital trial. Historically, prosecutors relied and I mean, you know, post-Reconstruction, post- giving the right to serve on juries and other important civil rights and liberties to Black Americans. The way that prosecutors tended to ensure that Black Americans did not serve on juries was by ensuring that they were not qualified by virtue of rules that made it impossible for them to get on the list of eligible jurors. That was a way to keep Black Americans from serving. As the law began to enforce the right of Black Americans to serve on juries, peremptory challenges became the alternative way of excluding Black Americans, that is by prosecutors simply remove them by objecting to as many times as they could, without having to give a reason. So in 1986, the United States Supreme Court decided Batson with the goal of changing that systematic exclusion of black jurors through the exercise of peremptory challenges.

Anne Holsinger 6:19

In 2020, the clinic published a report titled ‘Whitewashing the Jury Box: How California Perpetuates the Discriminatory Exclusion of Black and Latinx Jurors.’ And in that report, you found that intentional discrimination persists in the selection of California juries. The report evaluated 700 cases decided by the California Courts of Appeal from 2006 to 2018, involving objections to prosecutors peremptory challenges, and you found that in nearly 72% of cases, district attorneys use their strikes to remove black jurors. Could you explain the significance of the findings from that report?

Elisabeth Semel 6:58

Sure, let me take a big step back to 1986 and what the court did and why the findings in our report are meaningful. In 1986, the court, that is the US Supreme Court, adopted a three-part test to determine whether or not a peremptory challenge was constitutional, was, was lawful. And the test, these three steps required the defendant to show what is known as a prima facie case of discrimination, some evidence that discrimination was going on in the exercise of the strike, at which point the prosecutor had to come forward with what is called a race neutral reason – that is a reason that on its face, did not smack of racism. And finally, the defendant had to show that the discrimination in the exercise of that strike by the prosecutor was purposeful, that is intentional. When the court came up with this test, Justice Thurgood Marshall, who is, I would describe as pretient, you know, in almost every case, put his thumb exactly on what was right or wrong about the direction in which the court was going, commented that although this was an important step, it was in an adequate step. And he explained the inadequacy of the test in three ways, which really resonate in the study that we did in 2020. First, he pointed out that in situations in which Black Americans are disproportionately not being called to jury duty, whether it’s because the method of selecting jurors eligible to serve is disproportionately excluding them or because we are in parts of the country or parts of a county, etc, in which there are few prospective black jurors, or for that matter, prospective jurors of color period, that it would be very difficult to make this showing that the prosecutor had struck more than one or two or even three jurors of color. Secondly, he pointed out that this idea of a race neutral reason, the prosecutors would come up with very easy ways to give a reason that on its face looked neutral, for example, well, the juror lives in a particular neighborhood. Well, that doesn’t necessarily smack of race, unless you dig underneath it. Or the juror doesn’t have a college education doesn’t smack of racism, unless you dig underneath it. And finally, showing purposeful discrimination would be very, very difficult, because in his words, unconscious racism unconscious bias is really, especially today, even in 1986, the most salient feature of discrimination. So fast forward over these last 38 years, there have been many empirical studies of how Batson functions, this test, functions in the state and federal courts that have found that prosecutors continue to disproportionately use these peremptory challenges to remove Black jurors. And they are successful in doing so, for the very reasons that Justice Marshall identified. We saw in the early 2000s going up until about 2018, the United States Supreme Court reversed in several high profile Batson cases. They, the court, articulated legal principles about Batson, about how it should work, about how it should be vigorously applied, that are broadly applicable, but it did so in cases, and these were all death penalty cases, in which the fact – that is the exclusion of the African American jurors – were especially egregious and the court took pains to describe these cases as being almost one off the facts were especially egregious, which I would argue gave the lower courts, the state courts and the lower federal courts permission to distinguish those cases and say, well, for example, many of your listeners are familiar with Curtis Flowers’ case out of Mississippi, which involved Mr. Flowers being tried six times for capital murder, until ultimately, the United States Supreme Court reversed because of a violation of Batson vs. Kentucky. The facts in that case were, in many respects, different from the average criminal case, which isn’t to say that Batson violations don’t occur frequently, it’s just that these were almost like, you know, Batson violations on steroids. To my point, those extreme facts, or those unusual facts have allowed lower courts to say, your case doesn’t look like Mr. Flowers’ case, therefore, we don’t find a violation. But increasingly over the same period of time, judges and legal scholars, as a result of these studies, have acknowledged that Batson has failed, and proposed a series of alternative approaches. It wasn’t until 2018, that the state of Washington and that is specifically the Washington Supreme Court adopted a rule, a rule of court known as general rule 37, as a result of a very comprehensive study by a workgroup that the court designated and that rule was a game changer. That rule essentially tossed Batson out the window and adopted a series of procedures and approaches that make for a very different process in the exercise of peremptory challenges and the determination of whether they are lawful. It was that report in 2018 that was the impetus for the study that the death penalty clinic did and published in 2018. So I’m sorry for the long answer, but it’s important to understand that a lot led up to our decision to take a look at what was going on in California. So what makes our study, Whitewashing the Jury Box significant, is that it was the first study of the exercise of peremptory challenges in California. Second, what makes it significant is its consistencies with other studies, and I often say the significance is in the lack of surprise, that what we found was identical to what all these other studies had found about the persistent use of peremptory challenges by prosecutors, the persistent use to eliminate in disproportionate numbers, particularly Black jurors, and the willingness of the courts to condone that kind of discrimination under the Batson procedure. So that, that was the significance. We, we looked at not-, we looked at, maybe I’ll speak for just a second about those 12 years of court of appeal cases that we studied. We also studied three decades of California Supreme Court Batson decisions, almost all of those in death penalty cases. And we found that it had been more than 30 years since the California Supreme Court reversed a case involving the exclusion of a Black juror. The court in that period of time had decided 140 cases, 140 Batson cases, that had reversed only three. And when I say that the reversal for a Batson violation was highly unusual in California, again, consistent with other states, including Washington, where the highest court in the state had never reversed because of a Batson violation or had reversed only once or twice.

Anne Holsinger 15:19

What reforms would you favor to change the status quo and why?

Elisabeth Semel 15:24

Let me elaborate a bit more on the findings would observe you would know, that’s fine, which explained the reforms. One of the findings that we made, again, consistent with other studies was the role that implicit bias or unconscious plays in prosecutors’ use of peremptory challenges. And what I mean by implicit bias is the reliance on racial or ethnic stereotypes that exploit the historic and present day differences between the experiences of most white jurors and jurors of color those differences, particularly with law enforcement and the criminal legal system. And the way those unconscious biases manifest is precisely the way that Justice Marshall predicted they would. He pointed in Batson to the example of a prosecutor, exercising a peremptory challenge against a black juror based on that jurors demeanor. For example, a juror who, a black juror who is sitting in the courtroom with his or her arms folded, with no particular expression on their face, being described by the prosecutor as sullen where a prosecutor would not have described a white juror the same way. We found that demeanor-based, appearance-based reasons were the most frequent grounds that prosecutors relied on for striking Black jurors and Latinx jurors. Secondly, they routinely and successfully removed Black and Latinx prospective jurors based on those jurors’ experience with law enforcement, having been racially profiled, having been arrested, having developed some distrust of law enforcement, or having something as simple as the experience of a relative who was incarcerated or someone who had been arrested. These were frequently used reasons and they are reasons that in the words of Justice Liu really emphasize the demarcation in the experience between white Americans and Americans of color, not just Americans, anyone living in the United States. But I’m focusing here obviously on citizens because citizens are eligible to serve. The difference in those experiences is what is being exploited. We looked at a decade of training that district attorneys received in the exercise of peremptory challenges in the selection of juries. That is dozens of District Attorney training manuals. And what we found was that district attorneys were encouraged to rely on the very stereotypes I’ve been describing, stereotypes about an ideal juror. An ideal juror is in these training manuals, someone who is middle aged, someone who is what we would describe as a professional, that is someone with a college degree or greater; someone who earns a middle class or upper middle class income, owns a home, etc. Which, as one can easily understand results in the likely exclusion of a disproportionate number of people of color. They are told to trust their instincts literally in quotes to trust their gut. And what we all know about stereotypes is that they come from our gut, they come from our experiences often are our unconscious experiences, and they can be without awareness, frequently based on racial and ethnic stereotypes. We also found that this term ‘race neutral,’ the way in which the courts had described or identified what is race neutral, the reason, the definition, excuse me is so expansive, that anything short of a prosecutor admitting that he or she had excused a juror for race based reasons would suffice. The result was that prosecutors literally had a laundry list of approved race neutral reasons that they could use the kind of reasons I’ve just been describing, in case after case after case, were approved by California courts, by courts in other states, by federal courts as race neutral. Finally, the California Supreme Court was disregarding these newer Batson cases, the cases in which the United States Supreme Court was encouraging more vigorous application, enforcement of Batson, more as far as we could see falling on deaf ears of a majority of the California Supreme Court. So we proposed a series of reforms: First, that there’d be no requirement of a prima facie showing. That is to say that if a party, it could be the defense, it could be the prosecution, objected that the opposing lawyer was exercising a peremptory challenge that was influenced by race, that the next step would be that the court would call on that lawyer who exercise the challenge to state their reasons that in establishing that the challenge was based on race, or I should say, influenced by race, there would be no requirement that purposeful discrimination be proved. So that instead, the standard would be that the judge, as an objective observer, someone aware that explicit, implicit, and systemic bias had played a role in the selection of juries, would find that race was a factor, would find that race was a factor in the exercise of that challenge. And then, two more important points, just as Washington [state] did, we were proposing that we identify a series of reasons that would be presumptively invalid. So the reasons I’ve just described for you, such as a juror’s neighborhood, if the juror had children, but was unmarried, if the juror had had a negative experience with a law enforcement officer, knew someone who had, had a family member was incarcerated, etc. Those reasons would be presumptively invalid, and also reasons related to demeanor, so that the party that is the attorney who was attempting to strike a juror of color based on one of those presumptively invalid reasons, would have a higher burden to show that the reason really related to the jurors qualification to serve that is the jurors impartiality, and that race was not a factor. And lastly, the courts wouldn’t be able to speculate. And what I mean by that, is that another finding, again, of ours, but consistent with other studies, was that oftentimes what courts would do, if they were not satisfied with the prosecutors reasons, the court would say, well, yes, and in addition, I observed the following about this juror, so that the court would fill in the blanks, give reasons that the prosecutor hadn’t given in order to shore up the court’s ruling, that it was permissible to remove the black juror, the Latinx juror, etc. Those were the reforms that we proposed in the report and I should say that the report coincided with the introduction in the California Legislature in early 2020 of AB 3070. So, in essence, the purpose of our report, once we concluded it was to be this, the empirical vehicle, this study vehicle for the support of this legislation in California.

Anne Holsinger 23:42

So you started to give us a little preview, but I know you’ve been involved in some recent legislative efforts to eliminate racial discrimination in the criminal legal system in California. Could you tell us more about what California is doing to address racial discrimination during jury selection?

Elisabeth Semel 23:58

Yes, I mentioned the year 2020, which I’m sure is a year that every one of your listeners will remember. In some respects, I think the introduction of this legislation and other racial justice legislation in 2020 was not only, not accidental, sadly not accidental because of the events, because of the murder of George Floyd, and the events that followed it, but it also gave momentum, an opportunity to acknowledge aspects of deep seated enduring discrimination in our society, whether California or elsewhere, and for the legislature for the first time to take some significant steps. So AB 3070 that I just mentioned, was one of those pieces of legislation. And it did indeed reject Batson as the formula for assessing the legality, the lawfulness of peremptory challenges, and what I was just describing as the proposed reforms in our report, precisely, with some modifications that we can discuss if we want to get in the weeds but more precisely, the changes the reforms that the California legislature adopted that year, that dramatically altered again, the way in which we pick juries in criminal trials in California, those reforms are what became effective in 2023 in January, in California. They will become effective in civil cases, in 2026, again, which is to say became effective in criminal trials then will become effective later in civil trials. So that’s the major jury reform legislation in California. But in the same legislation, that’s excuse me, the same legislative session in 2020, California adopted the Racial Justice Act, which was an enormous sea change that affects particularly focuses on racial discrimination insofar as it leads to unlawful convictions and sentencing outcomes. One of the features of both pieces of legislation that excuse me that both these pieces of legislation have in common is that neither require proof of intentional discrimination. Both of them are based on the recognition that discrimination often happens for reasons that are of of implicit bias. So the Racial Justice Act, as I said, focuses on mechanisms that produce convictions and sentences in which race is an unacceptable plays an unacceptable role. And one of the differences between AB 3070, and the Racial Justice Act is, at least as we currently understand it, AB 70 applies prospectively, that means it applied to trials that occurred in January of 2023, going forward. The Racial Justice Act initially applied when it was first passed in 2020, only prospectively, but it was made retroactive in 2023, to capital cases. So now we can circle back to the overarching focus of this podcast. Importantly, that legislation now applies to death penalty cases, no matter how long ago they occurred. And the Racial Justice Act looks at individual actors outside of the courtroom. So the question is, was there implicit or explicit racial bias, or animus, it can be based on race, ethnicity or national origin, by individual actors outside of the courtroom, that could be the police, the prosecutor, defense counsel or expert witnesses in the case where there are things that happened in the case that caused an impermissible result, by which I mean conviction or sentence based on that conduct. It allows lawyers to bring claims based on conduct that occurs during the court proceedings by those same actors or by jurors, and this is where we can return to the jury selection issue. Was there conduct by a juror or jurors that demonstrated implicit or explicit racial bias? And that can apply in capital cases to trials that occurred before the effective date of the statute. And then there are two pieces of this, of the statute, and this is hugely important in capital cases that allow lawyers to bring evidence of racial bias in conviction or sentencing outcomes by looking historically and systematically, in cases in a particular jurisdiction, which we mean typically a county over the course of time. Was there conduct by the prosecutor, by juries by the courts, looking at a total of cases? In other words, looking at an aggregate number of cases, it may be 100, maybe 200, it may be more, in which we can show these kinds of outcomes based on implicit or explicit bias that were impermissible influences. That I think is probably a segue to another question about what’s going on in California, but I wanted to emphasize that these are very, very profound changes in the law in California and I also wanted to mention that we’ve now been living with, we’ve been relying on and implementing AB 3070 since 2023, so we have two years, two good years of information about how effective the statute is being and I can tell you consistent with what is going on in the state of Washington, we are seeing changes in the composition of seated juries. We are seeing more jurors of color, especially more Black jurors, or Latinx jurors, we are seeing prosecutors be much more hesitant and reflective about relying on these historically, on these reasons, excuse me that were historically associated with race and discrimination and discrimination based on ethnicity before they exercise a challenge.

Anne Holsinger 30:27

As you mentioned, there are other changes going on in California and so I wanted to ask you about a filing that occurred on April 9 2024, when the California Office of the State Public Defender, along with several civil rights groups, filed an extraordinary writ petition at the California Supreme Court. And they’re arguing that the state’s capital punishment system violates the state’s constitution because of its racially biased implementation. Could you explain the legal basis of the petition? And what evidence supports the claim that California’s capital punishment system violates the state constitutions equal protection guarantee?

Elisabeth Semel 31:04

Yes, this is a historic filing. It’s the Office of the State Public Defender, a number of civil rights groups representing exonerees, for example, in in capital cases representing Latino citizens, residents, people living in the United States, all. Eva Patterson, I should mention is also one of the petitioners who is a renowned civil rights lawyer in California, who has been instrumental in in some very important civil rights litigation in the state and outside the state. So it’s a wonderful collection, if you will, of interested organizations, and a very impressive array of lawyers and legal groups who are helping the the excuse me the litigation, not just the Office of the State Public Defender, but the Legal Defense Fund, the ACLU, and Wilmer Cutler, which is obviously a prominent law firm. So there’s a wonderful coalition of lawyers who come together to bring this petition. The petition appeals to that it is directed to the court’s original jurisdiction. Normally, as I’m sure your listeners know, cases start in the lower courts, and they work their way up to a state’s highest court or the United States Supreme Court, but there are circumstances in California in which the Court has original jurisdiction, and one of those is in matters of significant public importance. So the argument here is that the perpetuation of racial discrimination in the administration of the state’s death penalty is a matter of significant legal importance. That’s what permits the petitioners to come before the California Supreme Court originally and the legal basis for the petition is that the California equal protection clause that is our Equal Protection Clause – what I mean by that, just to clarify, is that we are protected in California, just as all people in this country are by the equal protection clause, the 14th amendment in the United States Constitution. And the Supreme Court, that is the US Supreme Court has construed, that is interpreted that equal protection clause in a certain way and there is a strong argument based on the kinds of decisions we’ve been talking about, such as Batson, that in the US Supreme Court, the equal protection clause will be understood to require proof of intentional discrimination in a particular case. California’s equal protection provision is different. It is an independent provision, and is dependent on the law in the state of California as a primary source for understanding what it means. And California has rejected the idea that only intentional discrimination denies equal protection under the Constitution. And that it may be that in California, we argue, of course, that it is in California, that the disproportionate impact the racially disproportionate impact of the administration of a law can give rise to an equal protection violation. So that’s the legal basis for the petition and the supporting evidence is what has to be categorized as massive and compelling. The petitioners have brought to bear 15 empirical studies that were conducted over a 44 year period, that is to say that each study covers a different timeframe, quite a number of years in each study, but collectively 44 years. Four of those studies are statewide looking at the entire state of California. 11 are conducted at the county level. They were conducted by 13 different researchers, and nine of them, including the three statewide studies were independently reviewed by Stanford Professor John Donahue, who was a leading empirical researcher, and looking at this collection of these nine studies, concluding that powerful evidence that racial factors have marred capital sentencing outcomes. That was the conclusion, the ultimate conclusion that he drew from looking at them. And when we look more specifically at what do these studies tell us about the influence that race has in our cap-, the administration of capital punishment in California, just in a global sense, the findings are that Black defendants are as much as 8.7 times more likely to be sentenced to death than all other defendants. Latinx defendants are as much as 6.2 times more likely to be sentenced to death in California than all other defendants. And defendants of all races are as much as 8.8 times more likely to be sentenced to death when at least one of the victims is white. These results, again, are consistent with findings in studies that have been conducted in state after state across the United States. So when I say as much as 8.7 times more likely in that first data point I gave you, what I’m saying is that there’s obviously a range in each of these studies, as to how much more likely a black defendant is like, is to be sentenced to death. But as high as 8.7% and all of these numbers are significant, they’re practically significant in terms of the influence of race in these outcomes. Let me just give you an example of a study with which I’m familiar because it involves a case that we’re working on in the death penalty clinic and it was conducted in San Diego County between 1979 and 1993. The findings there, or the odds that the prosecutor would charge special circumstances were more than three times greater when the victim in the case was white, and the defendant was Black. What I mean by that when I talk about the prosecutor, I mean, the San Diego District Attorney would charge special circumstances. What I mean by that is that in California, in order for a defendant to face a capital prosecution, the prosecutor has to seek, it has to excuse me, allege at least one special circumstance, which means something like a murder during the course of a felony, such as a robbery, or a multiple murder. So those are the numbers looking at what we call a dyad. In other words, the relationship between or a situation in which you have a white victim and a Black defendant, looking at the circumstances in which the victim was white, and the defendant was either Black or Latinx. In those cases, the odds were six to seven times greater that the district attorney would seek the death penalty compared to any other victim-defendant combinations. So the study is compelling in its results, it involves a huge period of time it that is essentially the entire time since the reinstatement of the death penalty in California, a great number of different researchers using robust but but sometimes different data, and different methodologies, all of which converge in these consistent findings across the state. I wanted to mention one other aspect of the study that is, from my perspective, also very important, and that is the role of death qualification in causing results that are skewed by race discrimination. Death qualification is the process by which jurors are selected in capital cases and it involves asking jurors their views on the death penalty, and it’s the only time jurors are asked their views which makes it very unique to me in jury selection across the country. The evidence again is consistent across time and geography. The death qualification disproportionately excludes jurors of color, but particularly and emphatically Black jurors, and so one of the aspects, of one of the pieces of evidence that is woven into this petition are studies that show the way in which this discrimination in the jury selection process unique to a death penalty trial also skews the fundamental fairness of trials, skews the propensity of jurors and juries, to favor conviction and to favor death in terms of outcome. So there’s a relationship between death qualification and peremptory challenges, which we could also talk about. The point here is that when we look across the administration of the death penalty, there are any number of stages or parts of the process in which race becomes an insidious and practically influential circumstance. Also, importantly, in terms of this petition yesterday, three amicus briefs, that is friend of the court briefs, were filed by three different groups. So we now have influential public figures weighing in on the importance of the California Supreme Court taking the case. A group of retired California State Supreme Court justices and judges, in their brief yesterday argued that the troubling evidence of racial disparities presented in the petition is a reason for the Court to hear this case, because of the Supreme Court’s institutional responsibility to confront serious legal claims of racial discrimination. In other words, going back to that initial reason that I raised, these are matters of great significance to the legal system and to the California Public. A group of current and former district attorneys filed a brief, citing the same evidence as a threat to their role as the guarantors of public trust, and legitimate, the legitimacy of our criminal legal system as the, as the actors that seek the death penalty, as the actors that prosecute these cases and defend these cases that is further prosecute them when they after conviction, and that this evidence is serious enough that it undermines the trust that the public is supposed to have in prosecutors. And then finally, a group of 18 state legislators asked the court to take the case, because the consequences of the kind of racial discrimination that the petition describes cannot be fully ameliorated through legislative action. In other words, the legislature has limited ability to fix these problems. And we talked earlier about AB 3070 and the Racial Justice Act, the legislature can chip away in some time significantly at the influence of racial discrimination, but if the thesis of this the legal argument in this case is correct, that the death penalty violates our state constitution, our legislature does not have the legal authority to repeal the death penalty. There are two institutions, if you will, that can take that action in California and one of them is the California Supreme Court. The other is the voting public. We know the Court is interested in this case, it ordered a preliminary opposition by the Attorney General to be filed on May the sixth and the petitioners reply is due on the 16th of May. So we have the first indication we have is that the court is taking this petition seriously. What will happen, what the courts action will be after that, to some extent depends on the Attorney General reply. In publicly, our Attorney General Rob Bonta has stated and I’m quoting here, that the death penalty has long had a disparate impact on defendants of color, especially when the victim is white. He has also said that California is moving toward ending the death penalty. So here in this situation, we have the Attorney General essentially confronted by his very public statements, which at minimum suggest that he recognizes that California has a structural problem with racial discrimination in the administration of its death penalty. So what is it that the, that the attorney general is going to ask the court to do? It would seem to me that he is in a very difficult position, we’re here to suggest that evidence that he has essentially acknowledged is meaningful doesn’t warrant the court’s consideration. The court in terms of options, the court has an option to decide not to formally hear the case after this briefing could simply dismiss the case. Hopefully, I’m not prognosticating, but I’m stating hopefully based both on the court’s initial order, and the Attorney General’s public statements, that the court will be will feel compelled to hear the case. It could then accept the case and decide the case on the pleadings, by which I mean, the petitioners pleadings before the court the evidence that has presented in its petition, it will present in its reply in whatever the Attorney General and other friends of the court present to the court, that is an option. And another option is that the court could accept the case and order or designate what we call a referee or a special master. In other words, a specific judge to hear the evidence to actually take evidence, hear from the experts in the case and reach a decision.

Anne Holsinger 46:01

Thank you. Is there anything else you’d like to share with our listeners?

Elisabeth Semel 46:05

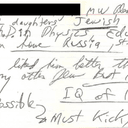

There are two very recent developments in California that further illuminate the pervasive influence of race discrimination in our state’s capital punishment system and underscore the imperative of a system wide response. This month, first development, four years after Santa Clara District Attorney Jeff Rosen decided that he would no longer seek the death penalty, he is moving forward with resentencing 15 individuals who are currently on death row from Santa Clara County, so that they will no longer be facing execution. He announced that he had lost faith in the ability of capital punishment to administer fair and equal justice. Mr. Rosen described the capital punishment system as antiquated, racially biased and error prone, a system that deters nothing and costs us millions of dollars and our integrity as a community that cherishes justice. The second significant even more recent development, in other words, as recent as this week occurred in an Alameda County case, that is presently in federal district court for review of its habeas corpus petition. The defendant in this case is Mr. Ernest Dykes. Mr. Dykes is a Black man sentenced to death in Alameda County in 1995. Now for decades, attorneys representing individuals sentenced to death in Alameda County have argued unsuccessfully, that prosecutors were exercising peremptory challenges to exclude Black and Jewish jurors. In other words, they were alleging repeated violations of the constitutional rule announced in Batson vs Kentucky. Mr. dikes is one of those individuals. A deputy district attorney in Mr. Dykes’ case, who was reviewing the file at the direction of the judge, found the prosecutors jury selection notes from 1995. The notes include derogatory comments by prosecutors about Black and Jewish jurors, indicating their intent to exclude them based on those prospective jurors’ identities. And in fact, no Black or Jewish jurors sat in Mr. Dykes’ trial. To give you an idea of how far back this goes, there was a review of 26 capital trials in Alameda County – trials that occurred between 1984 and 94. The review showed that the district attorney’s office, DAs in the Alameda County District Attorney’s office removed every juror who identified themselves as Jewish and almost 90% of those who had what were described as Jewish sounding names. In Mr. Dykes’ case, the DAs office disclose the notes to the defense and the court. The result was an order by the Federal District Court Judge of a review of all capital cases that are pending in the Northern District of California for evidence that prosecutors exercised impermissible peremptory challenges. According to a press release from the Alameda County DAs office, the office is not only reviewing the 14 or so cases that fall into that category, it is also looking at 35 cases of defendants on death row from Alameda County. DA Pamela Price has said this type of conduct undermines the integrity of every one of those cases. So again, I can’t underscore how unusual it is for a judge to order disclosure of jury selection notes, by, that is the prosecutor’s jury selection notes, I can’t underscore how unusual it is for the notes to be in the file decades after the trial, especially when they reveal the kind of intentional discrimination evidence in the, evident in the notes of Mr. Dyke’s prosecutors. What we really have here is the convergence of very vigorous lawyering and chance. And chance is not justice for men and women sentenced to death. One can safely argue that chances not justice for anyone in the criminal legal system. So these developments in Santa Clara and Alameda County really emphasize the importance of a system wide response. They emphasize the importance of district attorneys in other counties in the state doing this kind of investigation. But more importantly, they emphasize the necessity for the California Supreme Court to take the case filed by the Office of the State Public Defender, and other civil rights organizations and leaders and scrutinize at the level that this particular claim deserves, and this overwhelming evidence of a violation of the state’s equal protection guarantee. I hope that I’ve peaked for lack of a better word, the interest in DPIC listeners, not just in something I know that DPIC listeners are acutely aware of and that is the role of race discrimination in the administration, the death penalty, but to think more broadly, about, particularly its influence in the jury system. It’s not, it’s important to acknowledge that it is not just what happens after jurors get to the courtroom and we’re in the process of selecting them, whether it’s death qualification, whether it’s the exercise of peremptory challenges. There is a serious, systematic structural deficiency in the way we bring jurors into the court into the methods we use for ensuring and I would argue not ensuring that we are bringing everyone in who is eligible to serve and that we are defining eligibility that in a way that is inclusive and diverse and not discriminatory, whether it’s based on a juror’s income, a juror’s neighborhood, or the color of a juror’s skin. We just released a new report called Guess Who’s Coming to Jury Duty, that looks more broadly at these questions of the composition of our jury venires, and what we can do to better ensure that we do not continue to discriminate. One of the most important things that we can do on a state by state basis that has been done in cities like San Francisco and some other jurisdictions, including the State of Washington, which is making moves in this direction, is to increase juror pay. Because when jurors are paid an amount, such as they currently are in California, $15 a day, some states are a bit more many states are less, it doesn’t take an imagination, to picture who can serve on a jury who can afford to pay parking, who can afford to pay for a meal, who can afford to have their children not picked up from daycare or whatever obligations these jurors have, not to mention who can afford to go without pay for more than a day or two. So these issues that so profoundly concern the ongoing discrimination against people of color in this country extend beyond, as I said, peremptory challenges beyond the question of the administration of the death penalty to the very core of how our criminal legal system functions.

Anne Holsinger 54:07

Thank you so much for joining us today. If our listeners would like to learn more about the death penalty, they can visit the DPIC website at deathpenaltyinfo.org. And to make sure you never miss an episode of the podcast, you can subscribe to Discussions with DPIC on your podcast app of choice. Thank you so much, Professor Semel.

Elisabeth Semel 54:25

My pleasure. Thank you again for inviting me.